The U.S. funding bill for fiscal year 2019 passed last week is a mixed bag, but for international climate funding, there are some welcome developments.

International climate finance brings clear benefits, not just by helping recipient countries pursue sustainable development, but also closer to home, by boosting demand for U.S. clean tech exports and expertise and addressing root causes of national security threats. International support is also a key pillar of the Paris Agreement; developing countries promised to join rich countries in cutting emissions in exchange for financial assistance to support their efforts and to adapt to climate impacts. As we did last year, here’s a breakdown of what the latest funding bill does and doesn’t do for international climate action.

The Good News

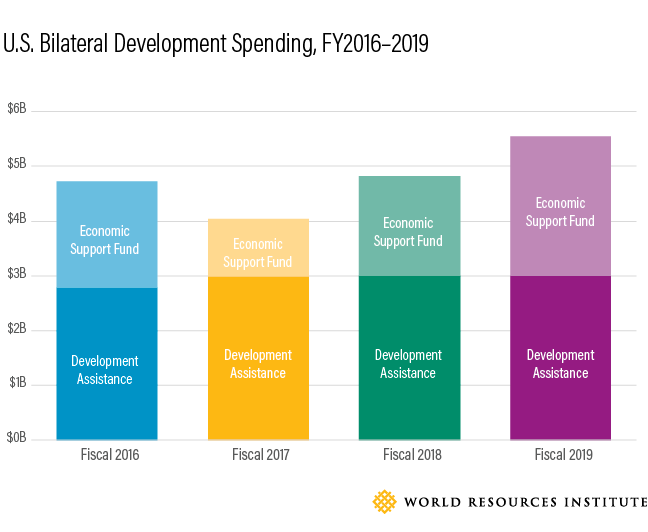

$776 million in bilateral allocations for environmental programs. A large amount of U.S. climate finance goes through its own aid agencies, primarily the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Overall allocations to the Development Assistance and Economic Support Fund accounts, which fund State and USAID’s development work, have increased in the past two years and are now above Obama-era levels. But in the absence of transparent reporting (the U.S. is one of only three developed countries not to have submitted its 2018 climate reporting to the UN), it is difficult to tell exactly how much of this goes to climate-related assistance. In a welcome move, this funding bill directs $776 million of this development spending to specifically target environmental goals, an increase of nearly $400 million compared to fiscal 2018. This can ensure development dollars are spent more effectively by taking the challenges of a changing environment into account, and gives Congress a bigger role in setting spending priorities.

$140 million for the Global Environment Facility (GEF). The GEF is the oldest international environmental fund, created in 1992, and supports a wide range of issues, from tackling illegal wildlife trading to chemical waste cleanup, and from promoting food security to building sustainable cities. Last year, the GEF’s coffers were replenished, as is the case every four years. At the pledging conference, the Trump administration announced it was cutting the U.S. pledge in half, hoping to excise what it thought was money for climate change. Overall, this would have left the GEF short of $300 million compared to the last replenishment. However Congress, which for years has supported the GEF on a bipartisan basis, allocated funding in this latest bill in line with pre-Trump years. In addition, the bill makes a specific statement of how much this will amount to over four years – $546 million. While this is non-binding, it does send a signal to the international community that this Congress intends to remain a top contributor to the GEF.

$1.3 billion for multilateral development banks: The U.S. is a major contributor to multilateral development banks such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, and the African Development Bank. These institutions are major providers of climate finance, and they have committed to increasing their climate finance even further. They are also aligning their broader portfolios with the goals of the Paris Agreement. The fiscal 2019 budget holds spending for MDBs stable at the same level as the previous year, and in line with what the U.S. has pledged to these institutions.

$29 million for the Montreal Protocol Multilateral Fund: This fund helps developing countries phase out ozone-depleting substances, several of which are greenhouse gases that pack atmospheric-heating power that far exceeds that of carbon dioxide. The Trump administration requested $32 million for the fund, in line with the U.S. commitment to the fund’s most recent replenishment, and while the Senate approved this level, the House of Representatives cut this back to $29 million. It is nonetheless positive that the fund is continuing to receive support, though it will require scaled up resourcing in future years to keep on track with the agreed U.S. share of contributions.

The Bad News

Nothing for the Green Climate Fund (GCF): This is a big year for the GCF, the largest international climate fund, which is undergoing its first replenishment. Countries are expected to come forward with new pledges to enable the fund to support developing countries in cutting their emissions and adapting to climate impacts. The U.S. is already behind in its contributions. President Obama pledged $3 billion to the fund in 2014 but was only able to deliver $1 billion before leaving office. Trump has opposed further funding. The GCF is growing its operations fast, and approved $4.6 billion for 93 projects in 96 countries in its first four years of operation. The Trump administration’s position has already diminished U.S. influence over the fund’s direction, and is part and parcel with its misguided policy of withdrawing from the Paris Agreement.

No dedicated money for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC): The IPCC is the expert body that produces regular reports synthesizing the international scientific consensus on climate change. Meanwhile, the UNFCCC hosts global climate negotiations to enable collective action on tackling climate change. Funding was cut completely in the fiscal 2017 budget and while the Senate has repeatedly asked — with bipartisan backing — for annual funding of $10 million (consistent with 2016 funding levels), the House rejected a specific allocation. Within the International Organizations and Programs budget line, $10 million is set aside for a variety of UN Environmental Programs, and it is likely the UNFCCC and IPCC will receive some funding from this. It’s disappointing that for the last three years Congress has been unable to properly allocate necessary funds for these two organizations, something it had done with little fuss for the previous two decades.

New Congress, More Funding?

The fiscal 2019 appropriations bill shows that some in Congress are working to ensure the U.S. continues to fund important overseas programs that help countries reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve their resilience to the impacts of climate change.

With a new Democratic majority in the House and a strengthened Republican majority in the Senate we are likely to see a different dynamic to negotiations on the fiscal 2020 appropriations bill. Congress has done a decent job defending against draconian climate funding cuts proposed by the Trump administration. They now need to scale financing to a level commensurate with the urgency of the climate crisis.