Last month, a 10-megawatt solar plant went online in Sumber Soum, in central Mongolia. New solar plant inaugurations may be commonplace in many parts of the world, but in Mongolia, this was a noteworthy development. The country of 3 million people has traditionally relied heavily on coal-fired electricity. Sumber Soum broke new ground by helping Mongolia move to energy solutions that reduce global carbon emissions and improve air quality and health prospects for local communities.

There’s another reason the solar plant broke new ground: It’s the first to be funded by a Mongolian bank, XacBank. Renewables like solar have high upfront costs and don’t generate returns right away. These projects therefore require long-term investment horizons. But in Mongolia, interest rates have historically been too high and loan periods too short to make local lending for solar feasible.

How did XacBank break this trap? With help from the Green Climate Fund (GCF).

The GCF is the largest multilateral fund dedicated to funding projects for cutting greenhouse gas emissions and helping communities adapt to climate change. In 2017, the GCF approved a soft loan of $8.7 million to XacBank. The relatively cheap, long-term loan from GCF made the financials work for the Mongolian bank.

Just 15 months later, the plant is online and feeding into the country’s central grid. It is now helping power Mongolia’s fast-growing economy and improving its people’s quality of life. While the country still has a long way to go in cutting emissions and reducing dependence on high-carbon activities, making green investment easier is a key step to shifting the economy in the right direction.

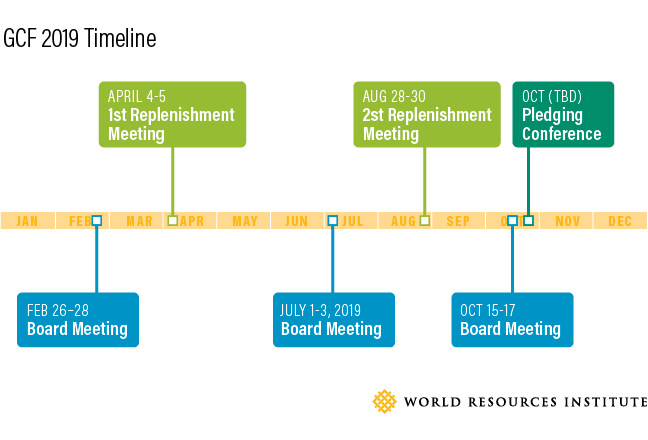

This year, as the GCF spends down its first pot of funding, the world’s governments gather to refill the coffers (replenishment). Germany and Norway have already announced that they intend to double their original contributions. With replenishment looming, it’s time to consider how the GCF is helping communities mitigate and adapt to climate change—and how it can do better.

A Game-Changing Fund

The GCF, with its mandate to accelerate climate action in developing countries, is critical to achieving the goals of the international Paris Agreement on climate change. Since it first started approving projects in 2015, the GCF has allocated $4.6 billion to 93 climate projects worldwide. The GCF is now one of the most visible and politically important institutions that channels climate finance to developing countries.

According to its mandate, the GCF is to promote a “paradigm shift towards low emissions and climate resilient development” while respecting priorities set by developing countries. For many countries, that shift will require transforming key sectors, such as energy, agriculture and transportation. Projects like the XacBank solar plant, with its innovative financing model, show how a well-timed and well-designed injection of GCF funding can unlock capital and break new ground, even in countries still reliant on high-carbon technologies.

The Sumber Soum project was not an exception. Consider India’s solar energy on rooftops program, implemented by India’s biggest rural development bank, NABARD. GCF’s $100 million loan will leverage $150 million from Indian investors.The program will unlock access to long-term and affordable financing for the construction of 250 megawatts (MW) of rooftop solar capacity in India, which equals electricity consumption of almost 290,000 households in India. This pioneering private sector-driven initiative will unlock private sector investment in the rooftop solar market and pave the way toward a sustainable bankable model in India and beyond.

The GCF is not only working to empower countries to cut emissions. It is also helping them adapt to the effects of climate change. For example, the GCF’s $39.3 million grant will help Morocco’s Berber women introduce climate-resilient and profit-making crops into their farming cooperatives. The project will allow women farmers to plant argan trees on a larger scale. Argan trees produce oil that is considered “liquid gold” in the cosmetics and food industries. The project is expected to improve the social and economic well-being of the local population and promote sustainable farming in more weather-extreme circumstances.

Becoming a Better Fund

But despite successes like Sumber Soum and Morocco’s women’s cooperatives, the GCF faced a crisis of confidence last year that called into question its ability to operate effectively. Key issues included how the Board takes formal decisions, the process and scale of refilling the coffers and outstanding policy issues relating to funding proposals (e.g. what kinds of costs the GCF will cover). While the GCF Board was able to rally at its last meeting in 2018, more progress will be needed to restore confidence in the fund. That is why GCF watchers will be paying close attention as the Board meets in Korea next week.

Two issues stand out: improving the decision-making process and selecting a new executive director for the Fund. As we have discussed in past blog posts, to ensure that the GCF can make timely decisions, there should be a clear procedure to call for a vote once the Board has exhausted all efforts to reach consensus. Regarding the new executive director, the GCF needs an effective leader who enjoys the trust and confidence of the Board—a people manager, strategist and decision-maker, all in one. In making its decision, the Board should not compromise on core qualifications.

More broadly, this year is critical for the GCF. An ambitious and successful replenishment is essential for the GCF to continue its work. At the same time, there is a need to improve GCF operations and show that it is back on track. The Board will need to clarify the GCF’s strategic direction and update financing policies to give clarity to projects seeking funding. The GCF also needs to strengthen its engagement with developing countries and financial actors to drive more investment toward implementing strategies built from the ground up.

The GCF is a game changer for many developing countries, as the examples in Mongolia, India, and Morocco show. And there is a lot to do this year to make the GCF a better and well-funded institution. So best foot forwards!