Picture a Guatemalan landholder who wants to put her land to good use. She plants her trees, waits for them to grow. She even receives a government subsidy for restoring her previously degraded land. Her trees remove carbon from the air, help clean the local river and provide habitat for many native birds. Yet when she goes to cut some of the trees for timber, she learns it is illegal to do so. A law designed to protect water quality prohibits cutting trees within 25 meters of a river. She decides to abandon the restoration project in favor of more profitable enterprises like growing sugar cane or cattle ranching.

While this story is fictitious, situations like this happen all the time in countries around the world. Paradoxically, laws that protect forests can hinder their restoration.

The global movement to restore degraded and deforested land is gaining steam. Through the global Bonn Challenge, countries have pledged to restore more than 160 million hectares of degraded land—an area larger than France, Germany, Italy and Spain combined. Governments have also signed onto regional initiatives like Africa’s AFR100 and Latin America’s Initiative 20×20.

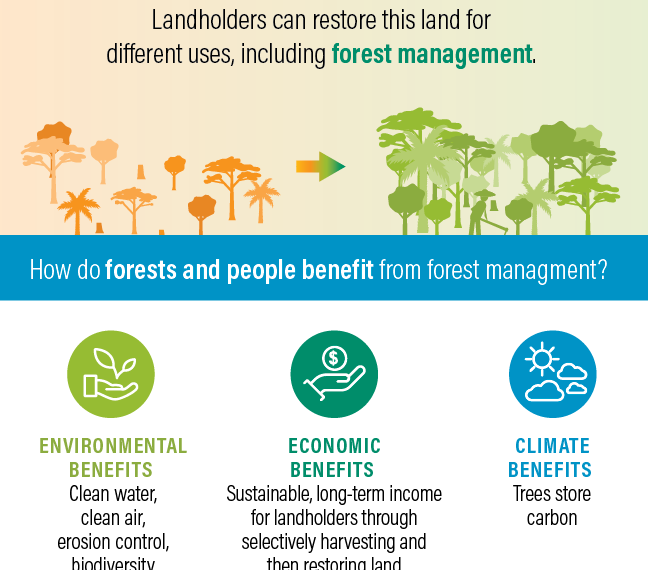

Governments need the support of private landholders and community groups to fulfill their restoration pledges. Some governments are pioneering programs that incentivize landholders to restore their land by growing and harvesting timber and other forest products. In many cases, forest management through small-scale timber plantations on restored land can be a long-term investment for the economy and the environment. Mature trees can be selectively harvested and replaced to ensure that carbon and soil remain in place and to provide a consistent income for landholders.

For these programs to succeed, laws and policies on forest protection, restoration and timber harvesting need to be conceived and applied in a holistic way. Here are three examples of incoherence in policy and enforcement jeopardizing local investment in restoration:

1. Rigid policies disincentivize restoration.

Our example from the beginning is tied to a Guatemalan law passed in 1997 which prohibits timber harvesting within 25 meters of a river to prevent soil erosion and water contamination. On the surface, this may seem like a forest-friendly policy, but it can backfire if these areas have already been deforested. If a landholder chooses to restore the area with trees, the law prevents him or her from harvesting the timber, even if the harvesting is done selectively, electively to maintain tree cover, new trees are planted to replace those cut down. Under these conditions, a landholder has an incentive to keep the land deforested or use it for agriculture and grow maize or other crops that are less desirable from a water quality perspective, contradicting the law’s broader objectives.

Here, the law has created an unfortunate situation where landholders cannot plant trees without forfeiting their right to harvest and benefit financially from their investment. These policies could, however, be tweaked to create special dispensations or incentives for landholders that are reforesting already-degraded land.

2. Ownership motivates restoration.

Until recently, farmers in Ghana had little incentive to reforest their land. As in several African countries, the state officially owns all newly-grown trees. Farmers had no legal right to harvest the trees they planted—and therefore no incentive to grow them.

To address this issue, the Ghana Forestry Commission (GFC) and the Ministry of Land and Natural Resources created a database where landholders can register the trees they plant, giving them proof of their right to harvest. The GFC will then verify the information through field visits. The policy change helps to clarify land-use rights and will be rolled out nationwide this year. This is one of a few changes to the forest code that will help Ghana reach its AFR100 restoration goal of 2 million hectares.

3. The high cost of legal compliance can discourage restoration.

A Costa Rican jungle. Flickr/seliaymiwell

Another disincentive for restoration is the lack of enforcement of illegal logging laws, which creates unfair competition for operators producing legal timber on restored land. A 2018 analysis of Costa Rican teak planted on restored land found that over a 17-year period, landholders received only 4 percent of the profit made along the teak value chain. Since those harvesting teak illegally don’t pay the taxes and fees that legal operators do, they have lower production and transaction costs. Sustainable timber suppliers struggle to compete, incentivizing plantation owners to cut corners on forest regulation compliance.

Again, governments could play a role in encouraging restoration. For one, they can make forest products grown on restored land more competitive by slightly lightening the burden of compliance on these landholders, while still maintaining core regulations to protect forests. Many governments have enacted laws that wood producers must follow, but those laws can prevent landholders dedicated to restoration from turning a profit.

And for restoration to work for landholders, illegal logging can’t. Governments absolutely should be concerned about illegal logging and pass strong laws to limit it. Each year, up to $152 billion in revenue is lost. Restoration can help meet the growing demand for timber without devastating forests, but only if legal frameworks punish illegal producers and adequately reward landholders who revitalize their land.

Creating Forest Policies That Enable Restoration

Everybody wins when forest-sector legal frameworks align with restoration goals: Degraded land is made productive again; landholders can make money; and governments collect more taxes and royalties from legal timber plantations.

Governments must balance policies that mandate the legal and sustainable management of forest resources with legal requirements that landholders can reasonably comply with. Otherwise, restoration commitments will be hard to achieve, and illegal timber could continue to occupy between 15 to 30 percent of the total international wood market.