Last week, six major multilateral development banks (MDBs) released their annual Joint Report on Climate Finance covering their 2018 operations. MDBs are key players in the climate finance architecture, providing around half of all international public climate funding, and play a big role in meeting the goal of mobilizing $100 billion a year in climate finance for developing countries by 2020.

As we did for the 2016 and 2017 reports, here’s our analysis of what’s good, what’s bad and what needs urgent attention. As always, it’s important to note that the Joint Report captures only a single year; we have therefore tried to contextualize the latest data with the trends arising over several years.

While climate finance from MDBs overall continued to rise, several institutions saw worrying drops, and it will take concerted effort to ensure climate finance continues to increase for the communities that need it most.

The Good

- Climate finance commitments hit another high. Total climate finance from MDBs reached $43 billion in 2018, a 22% increase on the $35 billion committed in 2017, itself the previous record. The World Bank Group and European Investment Bank (EIB) have already hit the climate finance targets they set for 2020, and the African Development Bank (AfDB) is on track for its goal.

- MDBs are paying more attention to adaptation finance. The share of adaptation in overall MDB climate finance increased from 23 to 30% between 2016 and 2018. This proportion varies widely by bank, with nearly half of AfDB climate finance going to adaptation in 2018, compared to just 8% for EIB and 12% for European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). The Paris Agreement calls for a balance in finance between mitigation and adaptation, so MDBs should continue efforts to scale up adaptation funding.

- Climate finance for the poorest and most vulnerable countries is growing. Last year, just 10% of MDB climate finance went to Least Developed Countries and Small Island Developing States. This year, the share grew to 16%, bringing it more into line with the share of developing countries’ population these countries account for – around 17%. There needs to be continued focus by MDBs on serving the most vulnerable countries since they have least capacity to adapt to the worsening climate emergency.

The Bad

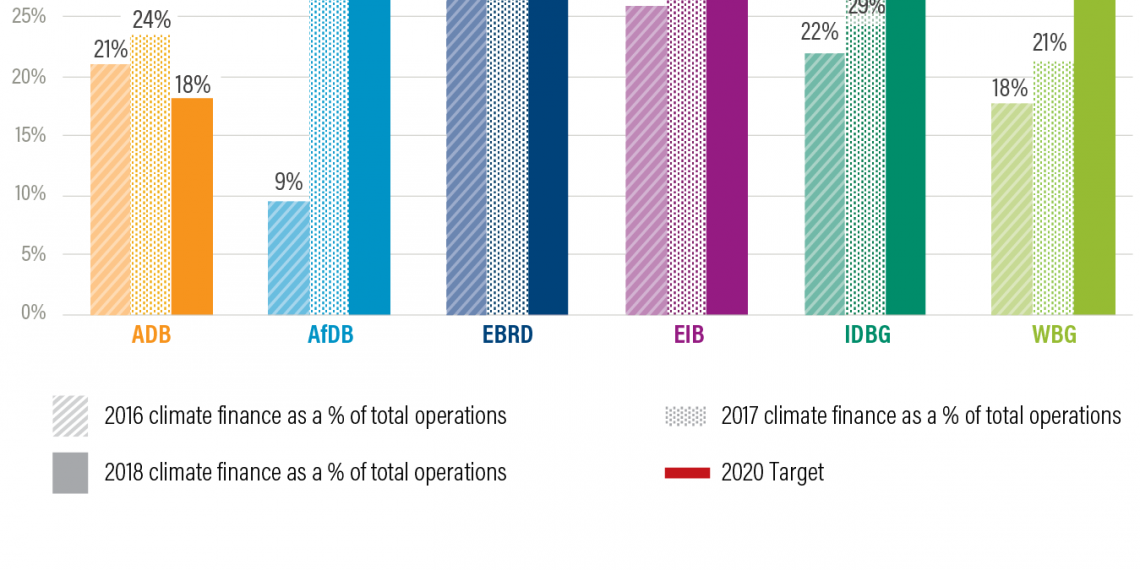

- Some MDBs seem to be struggling to scale up their climate funding. The Asian Development Bank (ADB), EBRD and Inter-American Development Bank Group (IDBG) all saw climate finance grow more slowly than their bank’s overall financing—meaning that climate finance as a share of total financing actually fell when it needs to be rising. Since most MDB 2020 climate finance goals are expressed as a percentage of their total operations, this puts their ability to achieve them in question. Furthermore, for ADB and EBRD, their absolute amount of climate finance fell by 23 and 17% between 2017 and 2018 respectively.

- Mobilization of private investment is still challenging. MDBs’ overall co-financing ratio, which measures the average amount each dollar of financing provided attracts in investment from other sources, is growing steadily, from $1.38 in 2016 to $1.47 in 2017 to $1.58 in 2018. MDBs devote a lot of attention to catalyzing private sector finance, yet for every dollar in MDB climate finance invested over the period 2016-2018, it mobilized $0.87 in co-financing from public sources, such as other development funders and national governments, and just $0.62 from private sources. While this may be a result of challenges tracking private finance mobilized, these results echo a recent Overseas Development Institute study that raises questions about MDBs’ and other development funders’ reliance on private investment to fill financing gaps.

The Urgent

- MDBs need to meet their 2020 targets and set post-2020 goals. With just one year to go, MDBs that have yet to do so – ADB, AfDB, EBRD and IDBG – need to work hard to ensure they meet the 2020 climate finance targets set back in 2015. Furthermore, several MDBs have also started to set post-2020 targets. The World Bank and AfDB have both announced a doubling of their climate finance over 2020-2025, while ADB has committed to a 2019-2030 target that also equates to doubling on current levels. Ideally, these targets should be complemented with goals expressed as a share of overall operations, to ensure that climate finance keeps up with banks’ overall growth. Other MDBs should set post-2020 targets with a similar level of ambition – at least doubling – and put a focus on getting finance to the most vulnerable communities.

- MDBs need to align their entire portfolios with climate goals. A 2018 report by WRI, New Climate Institute, Germanwatch and Fundación Avina called for MDBs to make sure not only that their climate-focused finance increases, but also that their overall portfolios are aligned with the Paris Agreement’s goals. It’s no longer enough (if it ever was) for financial institutions to scale up their ‘green’ activities. They also need to cease investing in high emissions activities driving the climate crisis and actions that do not take climate resilience considerations into account. MDBs can play a major role in advancing alignment by shifting their own resources and by pioneering best practices for other institutions to follow. At last year’s COP 24 climate negotiations, nine MDBs (the ones covered here, plus the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Islamic Development Bank and the New Development Bank), announced that they were developing a joint approach to align their activities with the goals of the Paris Agreement. The group of MDBs will present this at the COP 25 negotiations in Chile this December.

Before then, the UN Secretary General is convening a climate summit in September, where he is asking world leaders to increase their climate commitments. MDBs must not show up empty handed. For those MDBs that have not yet announced climate finance targets beyond 2020, the summit would also be a good time to do so. MDBs should also announce concrete actions towards aligning their portfolios, building on the World Bank’s leadership in ending their financing of oil and gas exploration and production.