Spearheading the alert ahead of the upcoming World Health Assembly in Geneva, UN Secretary-General António Guterres urged the international community to do much more to protect all those facing mounting mental pressures.

Launching the UN policy brief – COVID-19 And The Need for Action On Mental Health – Mr. Guterres highlighted how those most at risk today, were “frontline healthcare workers, older people, adolescents and young people, those with pre-existing mental health conditions and those caught up in conflict and crisis. We must help them and stand by them.”

That message was echoed by Dévora Kestel, Director, Department of Mental Health and Substance Use at the World Health Organization (WHO).

She pointed to past economic crises that had “increased the number of people with mental health issues, leading to higher rates of suicide for example, due to their mental health condition or substance abuse”.

Depression, anxiety, the ‘greatest miseries’

In a video message, the UN chief highlighted how psychological problems such as depression and anxiety “are some of the greatest causes of misery in our world”.

He noted how throughout his life “and in my own family, I have been close to doctors and psychiatrists treating these conditions”, and how he had become “acutely aware of the suffering they cause. This suffering is often exacerbated by stigma and discrimination.”

According to the UN guidelines, depression and anxiety before the COVID-19 pandemic cost the global economy more than $ 1 trillion per year.

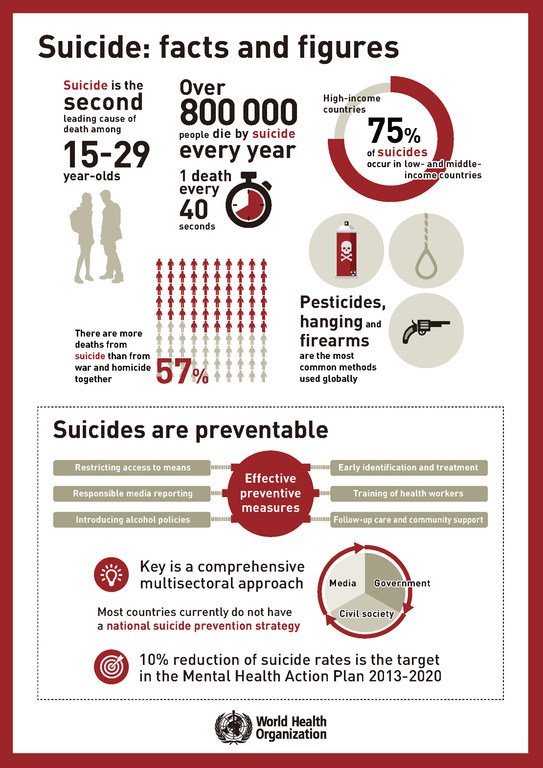

Depression affects 264 million people in the world, while around half of all mental health conditions start by age 14, with suicide the second leading cause of death in young people aged 15 to 29.

‘Less able to cope’ under COVID

The UN paper also highlights a warning from The Lancet Commission On Global Mental Health And Sustainable Development, that “many people who previously coped well, are now less able to cope because of the multiple stressors generated by the pandemic”.

All this is understandable, given the many uncertainties facing people, the UN policy brief notes, before identifying the growing use of addictive coping strategies, including alcohol, drugs, tobacco and online gaming.

Alcohol use is up

In Canada, one report indicated that 20 per cent of the population aged 15-49 have increased their alcohol consumption during the pandemic.

“During the COVID-19 emergency, people are afraid of infection, dying, and losing family members”, the UN recommendations explain. “At the same time, vast numbers of people have lost or are at risk of losing their livelihoods, have been socially isolated and separated from loved ones, and, in some countries, have experienced stay-at-home orders implemented in drastic ways.”

Specifically, women and children are at greater physical and mental risk as they have experienced increased domestic violence and abuse, the UN paper affirms.

At the same time, misinformation about the virus and prevention measures, coupled with deep uncertainty about the future, are additional major sources of distress, while “the knowledge that people may not have the opportunity to say goodbye to dying loved ones and may not be able to hold funerals for them, further contributes to distress”.

Increasing vulnerability

National data from populations around the world would appear to confirm this increased mental vulnerability, WHO’s Dévora Kestel said, citing surveys “showing an increase of prevalence of distress of 35 per cent of the population surveyed in China, 60 per cent in Iran, and 45 per cent in the US”.

Much higher levels of depression and anxiety than normal were also recorded in Ethiopia’s Amhara Regional State last month, the WHO official continued, pointing to the estimated 33 per cent prevalence rate of symptoms – a three-fold increase compared to pre-pandemic levels.

General symptoms caused by COVID-19 include headaches, impaired sense of smell and taste, agitation, delirium and stroke, according to the UN paper.

Underlying neurological conditions also increase the risk of hospitalization for COVID-19, it notes, while stress, social isolation and violence in the family are likely to affect brain health and development in young children and adolescents.

Social isolation, reduced physical activity and reduced intellectual stimulation increase the risk of cognitive decline and dementia in older adults, it adds.

Build back better healthcare

“We need to make sure that measures are there to protect and promote and care for (the) existing situation right now”, Ms. Kestel said. “This is something that needs to be done in the middle of the crisis, so that we can prevent things becoming worse in the near future.”

Data also confirms that medical professionals and other key workers have experienced significant mental health problems linked to the COVID-19 emergency.

“There were some surveys that were done in Canada where 47 per cent of healthcare workers reported (the) need for psychological support – 47 per cent – so almost half of them”, said Ms. Kestel. “In China, we have different figures for

depression: 50 per cent, anxiety 45 per cent, insomnia 34 per cent. Pakistan also, 42 per cent to…26 per cent.”

Huge needs in conflict-hit communities

The UN is also calling for action on mental health among populations fleeing violence, given that even before the COVID-19 outbreak emerged in China last December, the need for mental health and psychosocial support was “huge”, said Dr Fahmy Hanna, Technical Officer, Department of Mental Health and Substance Use at WHO.

“One in five people in these situations would need mental health and psychosocial support because they would have a mental health condition”, he added. “Yemen is not only the world’s largest humanitarian crisis, it’s also one of the world’s largest mental health crises, with more than seven million people who need mental health support.”

Institutional care overhaul needed

Many countries have shown that it is possible to close mental hospitals once care is available in the community, the UN paper states.

“In all emergencies, not only in COVID, there is a risk of human rights violations in long-term facilities”, said Dr Hanna. “There is a risk also of neglect in emergency situations in these facilities and there is a risk also in situations of disease outbreaks and of pandemic, of exposure of staff and residents to infections.”

A key part of the UN appeal is for mental health care to be incorporated into all Governments’ COVID-19 strategies, given that national average expenditure on it is just two per cent.

Such a move could help countries like South Sudan, “where there is only one mental health professional for every four million people”, said Dr Hanna. “Which basically means that someone living in the north of South Sudan, in a city like Malakal, need to take a trip to Juba, to the capital, of 2,000 miles that take him 30 hours to reach the only available service.”