In India, more than 700 million people depend on forests and agriculture for their livelihoods. And over 250 million, mostly tribal and indigenous communities, women, and marginal farmers, need forests for fuelwood, animal fodder, food security, and income. But these natural resources are under threat.

Climate change will only make the situation worse, potentially reducing agricultural incomes by up to 25% each year. This will leave more than 50% of India’s workforce vulnerable and its largely rural workforce in extreme distress.

That damage, though, can be reversed. More than 40% of the country’s territory, over 140 million hectares, could benefit from protecting forests and restoring farms, forests, and other landscapes. That’s how India can sequester 3 to 4.5 gigatons of above-ground carbon by 2040 and make progress toward achieving its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement on climate change.

A brighter future with healthy landscapes

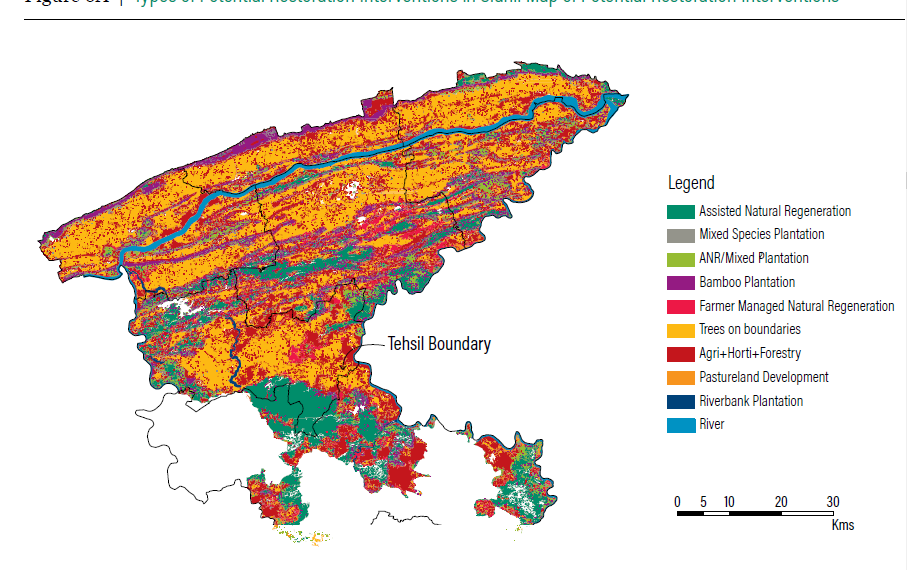

National leadership is important, but we know that restoration happens within individual landscapes. That is why we focused our analysis on the rural and climate vulnerable Sidhi District of Madhya Pradesh. This report applies previous research and adapts the widely used Restoration Opportunities Assessment Methodology (ROAM) to assess the environmental, social, and economic benefits that restoration can bring. By adapting ROAM, we could measure ecosystem services and livelihood benefits, land tenure, gender, and social inclusion. Landscape leaders throughout the world can apply this method to assess the true potential of restoring their lands for people and the planet.

Our analysis found that in Sidhi alone more than 300,000 hectares of land, or 75% of the territory, could benefit from more trees. Landscape restoration can help fight climate change by sequestering more than 7 million metric tons of carbon in forest areas alone, over 10-20 years. Landscape restoration can fulfil critical local demands by provisioning food, fuelwood, fodder and non-timber forest produce for dependent communities, controlling soil erosion and conserving biodiversity.

Achieving that opportunity will require some serious investment to grow nearly 40 million tree saplings in two years. In five to seven years, this investment could spur the development over 3,000 microenterprises that employ 30,000 people – including women, unemployed youth, and landless people – to grow, harvest, process, and sell high-value tree crops like bamboo, jackfruit, and moringa.

To unlock that potential, we uncovered the key people and organizations that govern the flow of information and funds, hold authority, and spur and mediate conflict – or the social landscape. By mapping that network, we found that while women and members of India’s marginalized Scheduled Tribes and Castes implement restoration, they are seldom key decision-makers. Without mapping the social landscape and including the voices of marginalized people, the newly restored landscapes would likely disproportionately benefit privileged groups.

By learning from these lessons, local decision-makers around the world can build more inclusive systems to manage land that maximize sustainable economic opportunities that create value for the most marginalized people.

Questions? Reach out to Ruchika Singh and Marie Duraisami.