The Torres Strait Islands, an autonomous part of Australia, are particularly vulnerable to the effects of the climate crisis, and extreme weather, including storms, rising sea levels and erosion, are a major threat to the indigenous people, who have inhabited the islands for some 70,000 years.

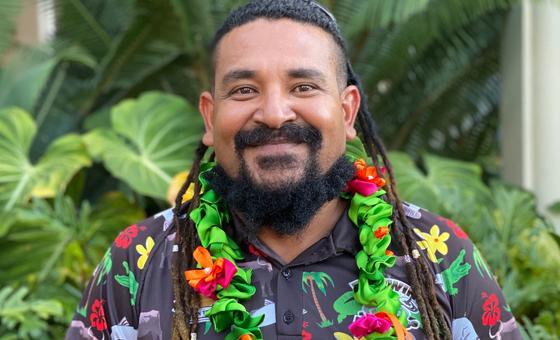

With the case ongoing, Mr. Molby and his fellow activists have been recognized as human rights leaders for their efforts to draw attention to the plight of their community.

“I come from Masig island, in the central part of the Torres Strait, which is between Papua New Guinea and the tip of Queensland.

There is something powerful about this teardrop-shaped island. There is an aura, which draws people to this place, which has protected us for thousands of years.

I am connected through this land to the birds, the sky, and the plants which surrounds us. I’m a part of the insects, the mammals, and the marine life, and they are a part of me.

We’ve been taught to live as one with nature, to protect and preserve it, in the way that it has been protecting and preserving us, our culture, and our tradition.

The right to protection against climate change

“We have the right to practice and carry on our traditions and culture, and the right to pass on what was passed on to us, by our parents, our grandparents, and our ancestors.

We have the right to pass that ancient knowledge to the next generation.

We’ve been through everything: the first cases of chicken pox, the first common flu – which practically wiped us out – and World War Two. But we survived.

Australia has an obligation to look after all Australians, and we have a right to remain on our Island.

Refugees in our own country

The Torres Strait Eight come from different islands but we all have the same passion to protect what belongs to us, for our future.

Otherwise, we won’t have a land to call home. We will be refugees in our own country. My children will have to be relocated, because the government will definitely remove us from homes.

So we said no. We’re not moving. What’s here is ours.

Loved ones washed away

Here on Masig, 30 to 50 metres out to sea, is where the beach was. There were villages all along the southeast coast.

You could hear laughter of children, while their mothers wove mats. The men would walk out on the reef to find food. It was a laid-back life, but a happy and safe life.

Then, we began to lose land to the sea, and the remains of our loved ones were washed away.

This affects us mentally, physically, and spiritually.

Marine life exodus

We used to have a lot of birds on this island.

Like the black and white pelican, the black and white booby bird, and others.

They don’t nest here anymore, and this is a sign that something is, you know, definitely is not right.

We used to have lagoons rich with seafood. At low tide, women could easily fish in their lagoons, whilst their children learned to swim with their big brothers and sisters, and grandmothers babysat the smallest kids.

Now. It’s a desert out there. The lagoons have gone, filled with sand, and empty of life.

Dangers in the deep

Making a living is getting harder. The major income on Masig is crayfish. Now, all the men have to go further out, and spend more on fuel.

It’s always dangerous to go out further, and the families of the husbands and sons out there fear for them.

There are a lot of dangerous things in the ocean, but the scariest thing is if the weather changes. You wonder if you will make it back home.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You can hear the full audio interview here.