When Eunice Marorongwe, a senior nurse at a rural hospital in Malawi, received a child patient with a serious leg infection, she was shocked at how her parents could keep her at home for a month, without getting treatment to save her life.

“It was at lunchtime at the end of last year when the 14-year-old girl came to the clinic with her right leg in a very bad state”, she says.

The leg could not stretch and, from the foot to the knee, it was very bad. It had turned into a green colour and was producing a very bad smell.

A tree branch pierced through the girl’s right leg, but her parents stayed put at home; not because they saw no need to rush to the hospital for treatment but because of fears and myths surrounding COVID-19.

Festering wound

“By the time they brought her to the hospital, the leg could not stretch and, from the foot to the knee, it was very bad. It had turned into a green colour and was producing a very bad smell”, says Ms. Marorongwe, who works at Mangochi District Hospital, about 250 kilometres southeast of Malawi’s capital, Lilongwe.

The girl was admitted after her parents were convinced the hospital could safely treat her.

“I am happy that we helped her, but I am worried that more people don’t come to the hospital for treatment. The situation worsened with COVID-19 as some are scared of being tested for COVID-19, while others are misinformed that they would get COVID-19 and die at the hospital”, says the nurse.

Limited access to health services in rural Malawi

Many people in rural Malawi fail to access health services due to a lack of facilities.

In Mangochi, where Eunice Marorongwe nurses, some patients walk for more than 10 kilometres to the nearest hospital. High transport costs for journeys taking over one hour, also hinder many.

“My work is very difficult when patients come very late. For every 10 patients I assist, three are in a very bad condition because they have delayed coming to hospital”, says Ms. Marorongwe.

Saving lives of the rural poor during COVID-19

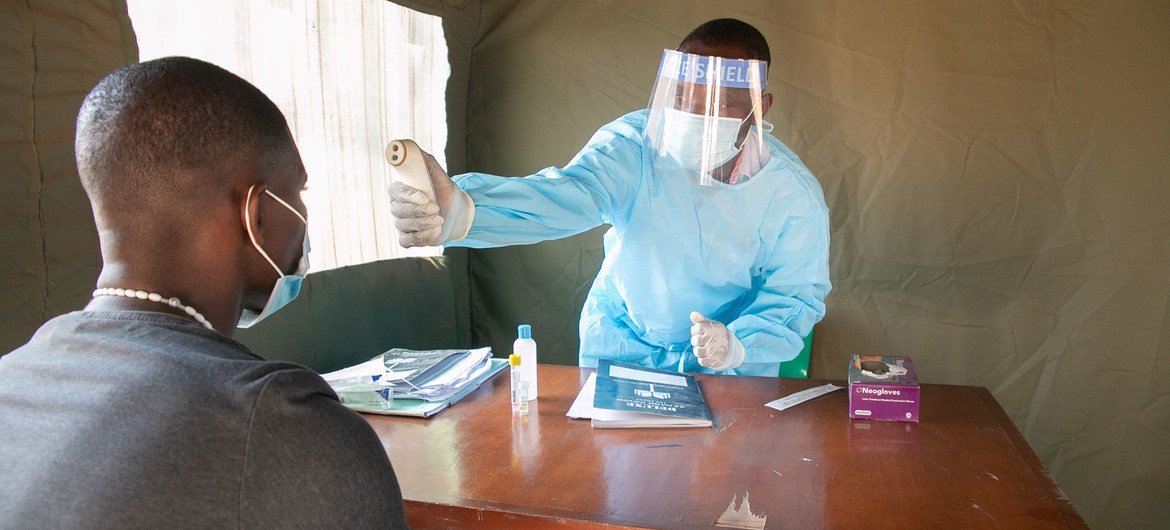

Last year, she assumed greater responsibility for providing healthcare to COVID-19 patients at the hospital’s emergency treatment centre, which was set up with United Nations support.

Similar centres were established at several rural hospitals across Malawi’s 28 districts, bringing COVID-19 healthcare closer to rural people who constitute 80 per cent of the population.

Despite Malawi recording some 34,000 COVID-19 cases and around 1,150 deaths since the start of the pandemic, Ms. Marorongwe believes many lives have been saved by the emergency treatment centres, where the UN also provided critical supplies, including medicines and oxygen concentrators.

Some of the 32,000 people who have recovered from COVID-19 in Malawi, were treated at these centres.

Our emergency treatment centre is a life saver. I am happy to see patients getting better and returning home. That makes me feel good.

“Our emergency treatment centre is a life saver. I am happy to see patients getting better and returning home. That makes me feel good”, she says.

To strengthen the rural health facilities, the UN also equipped 1,800 health workers with COVID-19 training and personal protective equipment (PPE). It has been regularly reaching over 14 million people with messages encouraging prevention and access to treatment for those who do not feel well.

A network of volunteers from over 300 community-based organisations – together with community radio stations, community leaders, a toll free line, and mobile phone messages sent through a dedicated platform – are used to communicate with people in remote parts of Malawi about the dangers of COVID-19 and the benefits of vaccination.

According to the UN Resident Coordinator, Maria Jose Torres, the most senior UN official in Malawi, without the support, the situation could have been dire for the disadvantaged groups.

Leave no-one behind

“When it comes to access to health care, nobody should be left behind”, says Ms. Torres. “Our interventions have ensured that those with disabilities, the youth, the elderly, the poor and children are able to access health care during the pandemic.

Mobile clinics and health surveillance assistants have been bringing health services to those living in the most remote parts of the country”.

Malawi’s Minister of Health, Khumbize Chiponda, says that with support from the UN and partners, “the Ministry of Health continues to send COVID-19 prevention and control messages to communities. Our laboratory testing and disease surveillance capacity has been increased to test more cases across the country.”

Beyond the health response, Malawi has also been mitigating the pandemic’s socio-economic impact in rural areas.

With UN support, the country sustained learning for 2.6 million children through radio education programmes when schools were closed; maintained essential food and nutrition services for 1.1 million children to prevent and treat malnutrition; provided cash transfers to more than 450,000 ultra-poor people, and rescued 720 girls from early child marriages.

COVID-19 vaccines supplied by the World Health Organization (WHO)-backed COVAX Facility have also now reached Malawi, a development which should in time make Eunice Marorongwe’s job slightly easier.

Find up-to-date figures here about the spread of the virus and the vaccination campaign in Malawi.