“Every two minutes a child dies from this preventable and treatable disease”, said WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

Every two minutes a child dies from this preventable and treatable disease – WHO chief

Malaria is a life-threatening disease caused by parasites that are transmitted to people through the bites of infected female mosquitoes. According to the UN health agency’s latest World Malaria Report, the estimated number of malaria cases remained virtually unchanged from 2015 to 2017.

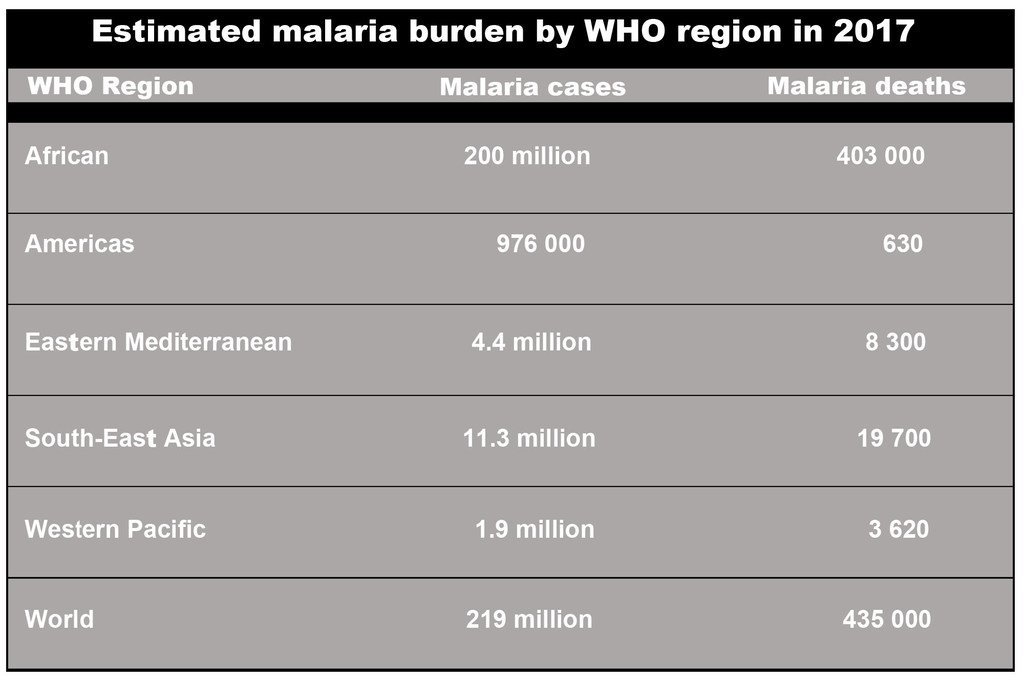

Moreover, there are approximately 219 million cases globally and an estimated 435,000 deaths.

In his video message, the WHO chief said the campaign “Zero malaria starts with me”, calls on political leaders, the private sector and affected communities to take action to improve prevention, diagnosis and treatment, stressing: “We all have a role to play”.

Commemorated every 25 April, World Malaria Day highlights the need for sustained investment and political commitment for malaria prevention, control and elimination.

An ominous numbers game

Tracking data and trends, the goal of WHO’s Global Technical Strategy to reduce malaria cases and deaths by at least 40 per cent by 2020 is off track.

Funding for the 2017 global malaria response remained largely unchanged from the previous year, which at $3.1 billion for malaria control and elimination programmes, is well below the $6.6 billion funding target for 2020.

According to the latest World malaria report, major coverage gaps have limited access to core WHO-recommended tools for preventing, detecting and treating the disease.

In 2017, 50 per cent of the at-risk population in Africa slept under an insecticide-treated net, a similar figure to the previous year and a marginal improvement since 2015.

Moreover, that same year, just over 22 per cent of eligible pregnant women in Africa received the recommended three or more doses of preventive vaccine, compared with 17 per cent in 2015. And from 2015 to 2017, only 48 per cent of children on the continent with a fever were taken to a trained medical provider.

Responding to the situation

In response, WHO and the RBM Partnership – the largest global platform for coordinated action towards a malaria-free world – recently catalyzed a new approach to intensify support for countries carrying a high burden of malaria, particularly in Africa.

“High burden to high impact” is founded on four pillars: greater political will to reduce malaria deaths; more strategic information to drive impact; better guidance, policies and strategies; and coordinated national malaria responses.

On World Malaria Day, WHO and other partners are promoting the “Zero malaria starts with me” campaign to keep malaria high on the political agenda, mobilize additional resources and empower communities to take ownership of malaria prevention and care.

“The time for decisive action is now”, stressed WHO.

Breaking it down

Last year in the Western Pacific region, there were more than 6000,000 cases of malaria.

From 2015 to 2017, WHO reported a 47 per cent jump in the preventable and treatable disease and a 43 per cent increase of deaths, largely due to outbreaks reported from Papua New Guinea, Cambodia and Solomon Islands which jointly account for 92 per cent of the malaria burden in the region.

“Mosquitos know no borders and will bit regardless of nationality or reason for migrating – IOM

“Urgent action is needed to address outbreaks in the highest burden countries”, underscored the UN health agency. “Ownership of the challenge lies in the hands of countries most affected by malaria and community empowerment is critical to support grassroots engagement across the region”.

‘Mosquitos know no borders’

The response to malaria should include all populations, according to the International Organization for Migration – including migrants, whether they are disabled persons, refugees or other vulnerable or displaced groups.

“Mosquitos know no borders and will bit regardless of nationality or reason for migrating” IOM said.

Managing health, mobility and frontiers means “much more” than monitoring a boundary check point between two countries, IOM pointed out. It is a joint commitment that recognizes “a series of spaces, actors and conditions that are part of the every-change and complex continuum of human mobility”.

Disease is easily transmitted in the overcrowded and unhygienic conditions that people on the move deal with.

While migration itself does not pose any health risks, IOM said that the adverse conditions on the migration route “do threaten the health of migrants and communities living in areas of transit, destination and return”.

The UN migration agency spelled out that any person linked to the migration cycle must be “informed, sensitized and prepared to prevent, detect and respond” to health threats.