Think about your “water footprint,” the water you use day-to-day. Drinking, brushing your teeth or doing laundry are things that probably come to mind. But the truth is that people eat way more water than they drink or use for household tasks. While the average person drinks 2 to 4 liters of water a day, it requires an astonishing 2,000 to 5,000 liters of water to produce the food that the average person eats each day!

Agriculture accounts for 70 percent of Earth’s freshwater withdrawals each year. As climate change exacerbates water stress and populations grow, rivers and lakes may not be able to keep up with demand. Here are five ways companies, farmers and consumers can lessen the food system’s impact on water:

1. Reduce food loss and waste.

Food is oftentimes mismanaged in fields, spoils before it can be sold, or gets discarded in grocery stores or homes. One billion tons of food are lost or wasted every year. A quarter of all agricultural water – over 17 percent of total water withdrawals – is used on wasted food.

Fortunately, people around the world are taking innovative steps to reduce food waste, such as developing new refrigeration technologies or using rather than discarding imperfect produce. The biggest thing consumers can do is plan. Write a shopping list for the week’s meals before setting foot in the store to avoid spur-of-the-moment purchases.

Retailers can shift consumer behavior, too. The House of Lords European Union Committee encourages stores in the UK to limit buy-one-get-one sales on perishable items. Similarly, the Consumer Goods Forum, a CEO-led organization of manufacturers, urges retailers to simplify their expiration date labels and include food storage tips on their packaging to make food last longer.

2. Shift diets.

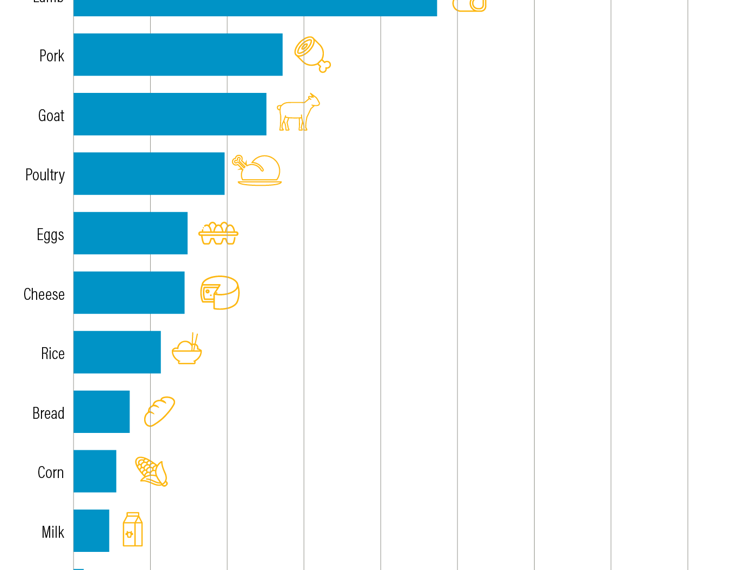

One of the most effective personal changes people can make to reduce their water footprint is to eat less water-intensive foods. In general, produce, grains and beans require a fraction of the water that meat, dairy and eggs do. For example, the water footprint of beef is 7,007 liters per pound, more than 50 times greater than the water footprint of potatoes (130 liters per pound). That said, nuts, fruits and vegetables can all require significant amounts of irrigation water, which can be problematic in water-stressed areas (see point 4 below). Plant-heavy diets have also been associated with a lower risk of heart disease, posing significant health benefits.

Food companies and restaurants can also help shift diets in more sustainable directions. Recent research from the Better Buying Lab shows that changing the language companies use to describe plant-rich foods is one of the most effective ways to influence consumer choice. For example, consumers are more receptive to foods marketed based on their look and flavor, rather than their health benefits.

Note: This graphic includes the total water footprint of each food, including blue water (irrigation), green water (rainwater), and grey water (volume required to assimilate pollutants)

3. Invest in nature-based solutions.

Poor management practices, combined with the effects of climate change, can exacerbate existing land and water challenges. For example, drought and deforestation can degrade land and deplete soil of its nutrients. Degraded soil is unable to absorb water efficiently. This requires farmers to use more water on their fields than they would otherwise, and makes lands more vulnerable to floods. About 65 percent of Africa’s land is experiencing some degradation, leaving farmers struggling to feed their families and make a profit with their crop yields.

One of the best ways to protect natural resources like water and soil while boosting food production is to employ nature-based solutions. Agroforestry, the practice of integrating trees into farms and pastures, boosts soil health, decreases soil temperatures and helps to maximize limited water supplies. This nature-based solution has been successful in Malawi, where maize yields increased by 50 percent after farmers planted trees on their farms.

4. Grow the right things in the right places.

Oftentimes crop yields are threatened by two main things: poor water management and drought. A great case study for this is rice, a staple food for over half of the world’s population. Though this crop alone consumes 40 percent of global irrigation water and grows best in heavily watered fields, too much water can create a breeding ground for methane-producing bacteria. Rice is also often grown in water-stressed areas, putting greater strain on limited resources.

Better water management can also reduce rice’s water demand. By draining rice paddies to a level just above the roots once each growing season, farmers in China and Japan have managed to increase crop yields, reduce planet-warming methane emissions and save irrigation water. However, many farms don’t have an irrigation system sophisticated enough to control the water on their fields this meticulously.

Though water management can help save water, some crops are still better suited for dry environments than others. Farmers should think strategically about the amount of water crops need before growing in drought-prone areas. Governments can respond by supporting further research, prioritizing and incentivizing water management, and making necessary tools and equipment accessible to local farmers.

5. Use the best practices and technologies in the field.

Regardless of where crops are grown, new technologies make it easier to protect water resources and grow healthy crops. For example, more than half of the world’s irrigated crops are grown in water-stressed areas. Drip irrigation is the best choice in these areas, as it is the most water-efficient method of irrigating crops. This form of irrigation delivers water directly to the root of the plants, instead of spraying it over the top or flooding fields with water. Not only does drip irrigation minimize the amount of water lost to evaporation and run-off, it leaves less water for weeds. If managed well, drip irrigation can raise crop productivity by 50 percent and use 60 percent less water compared to flood irrigation.

Though drip irrigation has benefits, rainfed agriculture still dominates globally. Managing rainwater well can be particularly challenging in areas with extreme wet and dry seasons. These farms could invest in better methods of rainwater capture and storage. Already, in countries like Ethiopia, these and other forms of water harvesting have been effective in reusing rainwater.

Though no one solution will completely solve the world’s water problems forever, making these five changes to our food system brings us a step closer to a sustainable water future.