by Dan Murtaugh, Bloomberg

Hydrogen, which has been touted as the fuel of the future much of the past five decades, may finally be on the verge of converting its potential to reality.

Governments, automakers and even oil and gas giants are part of a growing coalition pushing a larger role for the fuel as the world seeks to reduce carbon emissions while still providing reliable electricity to a growing population and powering complex industrial processes, the International Energy Agency said in a report released Friday.

The report underscores the challenges — existing production techniques are polluting and costly, while the gas itself is volatile and highly flammable — as the energy industry responds to increasingly urgent calls to decarbonize amid doomsday climate change scenarios. Policies must be put in place now to support early investments needed to reduce costs and scale up the industry, the agency recommended.

“Hydrogen has never enjoyed so much international and cross-sectoral interest, even in the face of impressive recent progress in other low-carbon energy technologies, such as batteries and renewables,” the agency said in The Future of Hydrogen report. “The current level of attention has opened a genuine window of opportunity for policy and private-sector action.”

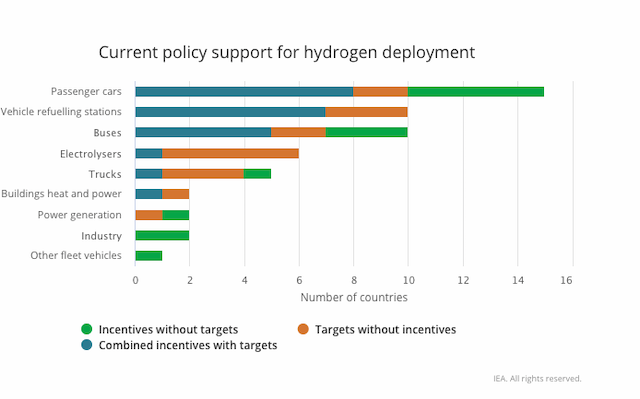

The IEA has suggested ways to push the market forward, including:

- Supporting research and development to bring down costs and creating financial vehicles to offset the risk of early investors

- Focusing first on increasing use at industrial ports, where existing production is concentrated, and on transport fleets along popular routes

- Launching international hydrogen trade routes

It’s not the first time hydrogen has been hailed as an energy savior. Interest surged in the 1970s for the fuel as a potential replacement in a transport sector rocked by oil price shocks, but the crude market moderated before any meaningful advances were made. The IEA says the difference now is that the driving factor — reducing carbon emissions — is less transitory than a commodity price spike.

Hydrogen can help decarbonize a range of sectors, from long-haul transport to steel-making, from which it’s otherwise difficult to remove emissions. It can also be stored and shipped and used to produce electricity, allowing countries with little space for wind and solar equipment to still receive carbon-free power.

Installing supportive policies and incentives now could help cut costs in the long run, according to the IEA, the same way that decades of subsidies and grants for photovoltaic cells and wind turbines helped make many renewable technologies cost-competitive with fossil fuels across the world.

“While deployment of solar PV and wind turbines was initially backed by direct government support systems and policies, investment in them now stands at $124 billion per year, mostly from private capital,” the agency said. “For the case of hydrogen there are also strong arguments for governments to take a more enabling approach.”