Sulayman*, an 18 year old from the North Bank region of The Gambia in West Africa, says that he will never forget what he saw, the day that he was caught up in a devastating tragedy: the ship he was travelling on sank off the Mauritanian coast, drowning at least 62 people who had left the country, in the hope of a better life elsewhere.

One of the most distressing details for Sulayman, is the fact that other vessels witnessed the tragedy unfolding, but chose to do nothing. “There were two fishing boats who saw we were sinking, but they didn’t help us”, remembers Sulayman. “They knew the area was deadly and yet, they did not help. You don’t forget that.”

Samba, who was also on board, * lost eight family members when the ship went down. Every morning, she says, she and her remaining family wake up and miss the loved ones they didn’t even have the chance to bury.

‘Shipwrecks are among the most traumatic life experiences’

Migration plays an important role in the Gambian economy, where almost half the population (48.6 per cent) lives in poverty. Some 90,000 Gambians live abroad, and the money they send back home accounts for more than 20 per cent of the country’s economy.

The World Bank describes the country as “fragile”, with several long-term development challenges, including an undiversified economy, poor governance, limited access to resources, and a lack of skills.

Every year, the search for an improved livelihood drives many young Gambians to attempt to reach Europe: over 35,000 Gambians arrived in Europe by irregular means between 2014 and 2018.

Data from the UN migration agency, UNHCR, shows that thousands of migrants have died attempting to reach Europe via the Mediterranean, often on vastly overcrowded boats that capsize or sink. This reached a peak in 2016, when more than 4,500 migrants died.

Gaia Quaranta is a psychologist working for IOM, the UN migration agency, in the West and Central Africa region. She told UN News that being involved in a shipwreck exerts a heavy mental toll.

“Shipwrecks rank among the most traumatic life experiences. Such events may put one at a greater risk for a wide range of mental health conditions often exacerbated by migration, another high-ranking stressful life experience”.

In late February, some three months on from the shipwreck, IOM led a series of activities in three North Bank communities – Barra, Essau and Medina Serigne Mass – designed to help Suleyman, Samba and other survivors, as well as their families and friends, to cope with the effects that the shipwreck is having on their mental health.

A dramatic recovery

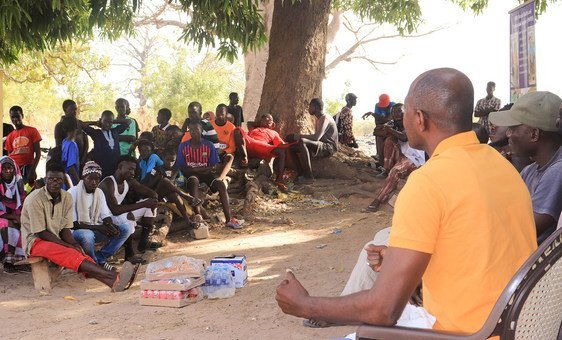

Led by a trained team leader, groups of survivors took part in discussions, in which they were encouraged to talk through the traumatic event they had been through, share positive and negative experiences, as well as discuss and suggest the strategies they employ to help them cope.

At the same time, family and community members met in separate groups to discuss how to support the survivors, and help to remove the stigma felt by returnees. As Ms. Quaranta explains, they are also likely to be suffering.

“It is important to be aware that the psychological impact of a shipwreck does not affect only those who were directly exposed (the survivors) but also those who witnessed such event or learned about it, (for instance helpers, family and community members). The impact on families is huge”.

Building on these discussions, survivors and other attendees watched actors perform a drama, showing some of the mental health challenges faced by returnees, families and other community members. This acts a form of group psychotherapy, helping the community to gain deeper insights into the way they feel, and make all members more resilient in the face of such tragedies.

These are just some of the ways that IOM helps those dealing with aftermath of traumatic migration-related events. “Different types of psychosocial support interventions have been put in place according to the needs identified”, says Ms. Quaranta, including “individual counselling, psychosocial support groups, referrals to specialized mental health services, psychosocial support to family members including women and children, and facilitation of peer support groups among the survivors and family members. It has been crucial to facilitate the grief process and to support the most vulnerable people”.

Helping communities to help themselves

The initiative involved training volunteers in each community, equipping them with the tools to support families in identifying symptoms of distress, as several different factors determine the likelihood of survivors needing mental health and psychosocial support: “Age, sex, length of time to receive health services, post-migration difficulties, social support, religion, and resilience may be potential predictors or protective factors to psychological distress”, says Gaia Quaranta, adding that they are “essential to identify who could be most at risk of developing trauma-related disorders, such as PTSD, anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders”.

The activities in the North Bank communities came to an end after three days, but the effects should last much longer. Evans Binen, an IOM mental health and psychosocial officer involved with the project, explained that it could help to build the foundations of a more resilient community, and lead to “healing among survivors, enabling durable family support mechanisms, encouraging community proactiveness to the needs of survivors, and promoting positive perceptions of returnees”.

Nevertheless, even with the knowledge that more people are likely to drown in the hope of reaching a new home, it is likely that Gambians will continue to try: “it is difficult to predict this but despite the adversities of the migration journey, a few returnees most probably will attempt the dangerous journey again”, says Ms. Quaranta, “especially given the persistence of post-migration life difficulties in their country of origin”.

*The names of survivors have been changed.