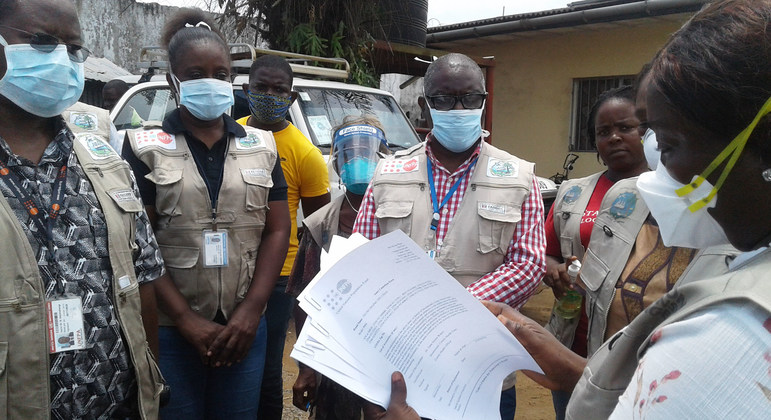

UNFPA has been recruiting hundreds of contact tracers from local communities who are supporting health authorities in the most affected areas by identifying everyone who has been in contact with an infected person, monitoring their health for symptoms, and referring suspected cases for testing.

“The work of the contact tracers is critical to breaking the chain of transmission of the disease in Liberia”, said Dr. Bannet Ndyanabangi, UNFPA’s representative in the country.

Shame, stigma and mistrust

Liberia has reported just over 100 cases of COVID-19 as of Friday. The disease was first confirmed there on 16 March. A week later, authorities declared a public health emergency and requested UN support.

For UNFPA, the situation was an eerie reminder of the Ebola epidemic that devastated Liberia, as well as Guinea and Sierra Leone, between 2014-2016. During that crisis, UNFPA worked with the Liberian Government and other health partners to implement contact tracing.

Although there are clear differences between the two outbreaks, UNFPA said some issues are the same, including shame, stigma and widespread mistrust in the community.

A tough job

In response to COVID-19, the Liberian authorities have implemented movement restrictions. Neighbouring Montserrado and Margibi counties are the epicentre of the outbreak, and residents there face more stringent quarantine measures.

Contact tracers are urgently being recruited, trained and deployed. In addition to identifying and confirming infections, their duties also include teaching people about infection prevention.

“It is not easy to work as a contract tracer, especially when there is still a high level of denial and stigmatization at the level of the community”, said Octavius Koon, a contact tracer who has been assigned to follow five mortuary workers who had been in contact with a body that tested positive for COVID-19.

To combat this mistrust, UNFPA is recruiting contact tracers who come from the most affected areas and deploying them within their respective communities. Still, they have to battle mistrust and misinformation.

“Some of the contacts we are working with do not want to be identified by community members, fearing stigmatization. Some of them also believe it is a waste of time to keep checking on them for the period, 14 to 21 days, when they are not ill”, said Mr. Koon.

“You sometimes realize that people would choose to lie or mislead you.”

Safeguarding health and welfare

Contact tracers also know that in doing their jobs, they are putting their own health at risk. Mr. Koon said strict adherence to guidelines and protocol offers some reassurance.

“The issue of personal safety cannot be taken for granted,” he added.

UNFPA has praised the contact tracers as they are essential for safeguarding the health and welfare of their communities.

“UNFPA appreciates their efforts because, as frontliners, with direct contact with potential COVID-19 infected persons, they are getting involved with the fight against an infectious disease that may put their and their families’ lives at risk,” said Dr. Ndyanabangi the agency’s representative in Liberia.

Today, there are more than 200 UNFPA-supported contact tracers working with the Montserrado County Health Team, which covers both Margibi and Montserrado counties. Efforts are underway to increase that number to 400 tracers in the coming weeks.

UNFPA has also contributed four pickup trucks, five motorbikes and 60 mobile phones to the National Public Health Institute of Liberia, to support surveillance efforts.