A tiny piece of coral is stuck to a thin sheet of plastic, and submerged in a tank at the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology on Coconut Island in Kaneohe Bay, on the island archipelago. This is part of a unique process which includes the cryopreservation [the use of very low temperatures to preserve living cells and tissues] of sperm, larvae and tissue, to create what has been called the “Book of Life” for coral.

Marine biologists, working on land and in the water, collect sperm and eggs from reefs during their annual spawning events, in the warm tropical water surrounding palm-fringed Coconut Island, and then in labs, where they prepare the coral for cryopreservation.

Ground-breaking techniques

Mary Hagedorn, a senior research scientist at the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, leads the team at the Institute which is pioneering these techniques.

“Cryopreservation is a relatively new field of science originating in the late 1940s, but was only first used to preserve human embryos in the early 1980s and then eggs at the end of the 90s,” she told UN News on a visit to Coconut Island.

“We have been working for the last 16 years on adapting those techniques to successfully preserve coral sperm, and also coral larvae, to store in living frozen bio-repositories, and help restore reefs now and potentially reseed the ocean in the future. We’re really collecting the Book of Life for coral reefs, and that’s significant.”

Coral reefs across the world are being threatened by climate change. The UN Environment Programme (UNEP) estimates that about 25 to 50 per cent of the world’s coral reefs have been destroyed and another 60 per cent are under threat.

Warm, acidic oceans, and coral ‘heart attacks’

As oceans become warmer and more acidic, the corals are bleached, an event which Mary Hagedorn compares to a person suffering a heart attack. “If bleaching happens on an annual basis then corals may ultimately die off,” she said.

Corals are animals that create their own skeleton to help support them. These animals live in shallow warm waters around the world using sunlight to synthesize their sugar-based food. Reefs are not just “beautiful ecosystems” renowned for their biological diversity, according to Dr. Hagedorn, they are also crucial to life on Earth. “Almost 25 per cent of all marine life lives on a reef at some point and so without them many species of fish that we eat wouldn’t exist. Corals provide a natural protection for our coastlines, for example against tsunamis. They also support people’s livelihoods in the form of fishing and tourism and contribute 350 billion annually to the global economy. So, there are many reasons we should save them.”

Researching for the benefit of future generations

A small international team of marine biologists is based in the lab on Coconut island, which sits on top of a coral reef and is surrounded by many more, making it possible for the scientists to collect samples in a small dinghy, or by snorkeling. They also travel to many tropical countries around the world to help preserve their reefs including in Australia, Singapore and French Polynesia, among others.

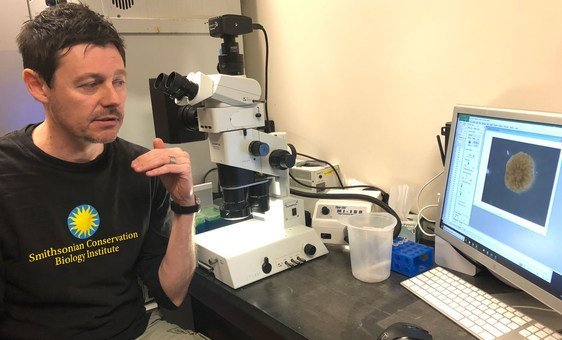

In the institute’s laboratory, Australian postdoctoral researcher Dr. Jonathan Daly examines polyps, individual coral animals, under a microscope.

“Corals have a very restricted annual cycle for reproduction (just a few days) and so there is a very brief window to collect their sperm and eggs in the field, and bring them into the lab for cryopreservation,” he says, adding that “today, coral reproduction is impacted very heavily by warming oceans.”

The material gathered by the team is stored in frozen biorepositories and it’s hoped ultimately that other marine biologists in laboratories worldwide will eventually be able to preserve corals where they work. This would save the biodiversity and genetic diversity of their local coral reefs and help to create the Book of Life for corals that Mary Hagedorn talks of.

This means that, if one of the many thousands of coral species found around the world becomes extinct, then potentially it could be regrown from the frozen biorepository.

The role of the ocean in economic and social development

“Our job is really not about today, it’s about 200 or 500 years from now when, hopefully, our oceans have returned to pre-industrial conditions,” says Mary Hagedorn in her laboratory. I’ll never see the fruition of our work in my life, nor will my students or their students. Nevertheless, we have set this whole thing in motion, and as a scientist, I know we’re doing something that really is good for the planet. However, it is very critical that we do this work now, while corals still have robust genetic diversity.” Mary Hagedorn and her colleagues were interviewed as part of a photographic project called “Dignity at Work” which is being undertaken across the United States by the UN’s International Labour Organization (ILO).

Oceans’ role in economic and social development

Kevin Cassidy is the Director of the ILO Office for the United States: “We have seen the far-sighted and truly inspiring work on coral reefs by Mary and her team,” he said, explaining the key role the ocean plays in economic and social activity.

“When one is fishing for seafood it creates income for the fisherman, his workers, more jobs in wholesale markets and shops, purveyors and transport workers, chefs and waiters serving food, patrons at restaurants and taxis.